Yesterday marked twenty-nine years since the Challenger launched into a cold blue heaven only to explode into a series of chaotic contrails, resulting in the tragic death of all those on board–six astronauts and one school teacher. It was the first time a civilian had ever ventured into space. The shuttle shot up and then it fell apart; from the orange and white fireball, the debris fell into the sea below.

I was nine years old, in the fourth grade at Foothill Elementary in Boulder, Colorado; the year was 1986, but mostly I call it the worst year of my life. This was the same year I read The Headless Cupid by Zilpha Keatley Snyder and promptly created my own “Calendar of Ordeals” based off the one ordeal the children do in the book to be initiated into the Occult. For those of you who don’t know, my novel Fig was originally titled, The Calendar of Ordeals, a topic I’ve written about before so let me circle back to what I was saying. Let me follow the looping trails of smoke that escaped from the space shuttle twenty-nine years ago and one day back to the post I’m writing now (memory is such a funny thing). While the book is no longer titled, The Calendar of Ordeals, there is still a chapter that goes by this name, and in this chapter, a nine-year-old Fig echoes a nine-year-old me.

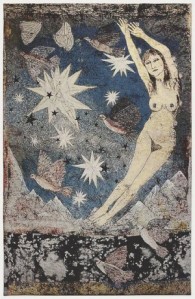

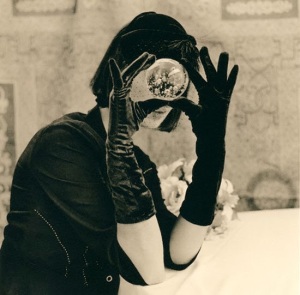

At this point in the book Fig knows her mother has schizophrenia, and having read Keatley’s book just as I did, she’s created her own calendar of daily sacrifices hoping that by doing so she can and will cure Mama. I was not trying to cure anyone. When I didn’t touch metal for an entire day, my mission was entirely self-absorbed. I was trying to cope with loneliness. I was trying to remedy my melancholia. I was living in a world where I seemed to have no control and the Calendar was my attempt to bring a sense of order into my life. Raised by an agnostic and an atheist, there was no god to turn to. I had to learn to deal with my problems on my own. That said, I did know about magic. Magic was the key ingredient to the books I loved to read when I was nine. These books weren’t just for children either; my library was full of texts on witchcraft; books full of spells; books about persecuted girls and women. The Occult. Hexes. Familiars. Scrying. Crystal Balls. Magic Mirrors. Gypsy Caravans.

And so I made the calendar: I used crisp sheets of stark white drawing paper and black felt tip pens. I taught my hand, via hours of practice, to scroll across the page leaving elegant marks. I mimicked the art of Edward Gorey and Aubrey Beardsley. Through the months and weekdays, the stylized pen(wo)manship was created by a series of tendrils, spirals, and meanders. I particularly honored the capital letters, as is the tradition in children’s stories and fairy tales. The “J” in January for January 28th, 1986 choked on the flower-laden vines that twisted and turned around it like a snake. Any “O” was filled with a night sky, a sharp crescent moon, a scattering of stars, I spent hours making The Calendar of Ordeals. A secret, it was something holy. And it required devotion and ritual.

In Selah Saterstrom’s book, The Pink Institution, a young female narrator finds an eraser shaped like the cartoon character, “The Transformer.” She promptly decides the eraser is god. She keeps god a secret as I did the Calendar. She takes god out when no one is looking. She puts god into her mouth. The compulsion leaves her satisfied and the compulsion leaves her feeling guilty. This is magical thinking. Today I brought a basket to class full of household tools: a hammer, a pair of pliers, a sachet, a wire coat hanger, a Maglite, a hand broom, a letter opener, a Mason jar, a telephone, binoculars, a screw driver, scissors, a mirror, and a metal ruler. The name of each item was written on a piece of paper, folded, and placed into my husband’s bowler hat. Today we read the excerpt from The Pink Institution and then my students blindly drew a tool from the magic hat and were instructed to turn their objects into god. The followers of the coat hanger hang their problems on god. The “Holy Maglite” (which ironically, and perhaps quite significantly, it’s been called before in a different workshop) dispelled sin via illumination. Those who’d been living in darkness had not known that they lived in the dark until they saw the light. When the flashlight stopped working, the world went dark, and the followers have no choice but to make a pilgrimage to Ontario, Canada in search of batteries. Secrets and rituals are the most potent ingredients when writing a story of any kind. People perform rituals around places of threshold. Someone with OCD will lock the door three times before she can leave the house. Sometimes these thresholds are more figurative than they are literal. Sometimes the threshold is growing up.

The Calendar of Ordeals was my god. And Fig’s as well.

In the book, Fig’s teacher brings a television set into the classroom so they can watch the live broadcast of the launch. When I described the tinfoil wrapped rabbit ear antennas, I wasn’t “seeing” the television I had at home when I was nine, but the one I had in Tennessee around the time my daughter was born. This is an emotional truth traveling through an object or image, but I’m getting ahead of myself.

I don’t remember a television in my classroom that day. The day a woman my age now tried to leave this world for another; the day she died doing so. The day she went to a whole other world as in: “the other side.” I don’t think we were going to watch the shuttle leave. I don’t know what the lesson plan was supposed to be. In the book, Fig and her classmates are instructed to sit in a half-moon on the floor to watch the lift-off. It is important to note that most of the ordeals followed by both Fig and I were all about avoiding contact with the world around us. We didn’t just avoid metal or the color white. There were days we couldn’t walk on cement; days we couldn’t touch wood; and there were days when we couldn’t speak or eat. It was difficult to get to school. To get through a closed door. It was difficult to communicate. Having been hurt by the world, and the people in it, we were terrified to make contact with it or them again. But I think we were also trying to see whether or not we existed.

In the television show, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, there is an episode about a girl at Sunnydale High who becomes invisible because no one ever “saw” her. In the Creative Writing I class I’m teaching this semester we’re covering figurative speech right now–metaphors and similes and personification, oh my! Along with the Saterstrom exercise and the objectification of god, we read Sylvia Plath’s poem, “Mirror,” discussed the myth of Narcissus, and then we wrote our own poems from the point of view of our own mirrors. We personified these reflective objects. We anthropomorphized these items and through the detachment of this process we then reexamined ourselves through an outside eye. Meanwhile, the current series of (W)rites of Passage is called, “Discontented Winter” in which we are embarking upon our next theme: Gender. Based on the Buffy episode, the participating writers are supposed to write a narrative about a person who becomes invisible as a result of his/her/their gender.

The real challenge of the Calendar for both Fig and I were the days where we weren’t allowed to avoid the world. Sometimes the Calendar forced us to interact, and in the chapter titled, “The Calendar of Ordeals,” the day the Challenger explodes above the Floridian sea, the ordeal dictates that Fig must touch other people as much as she can. This ordeal is an important one. A true sacrifice because it’s an idea she can’t stand. As she sits amidst her peers in front of the TV she realizes it’s now or never. But also, she is trying to reach out. She is trying to make contact with the “other.”

Fig is just about as popular as I was in the fourth grade–as in, we were both the biggest outcasts not only in our class, but our entire school. Fig’s mother is schizophrenic, and everyone knows it. They know she’s tried to kill herself; they know that it was Fig who crucified the Barbie at school in the second grade. And to top it off, Fig’s parents aren’t like the other parents in Douglas County. While Daddy did grow up on the farm where Fig lives with her family, her parents are trying to convert it to all organic. Daddy left Kansas to get an Ivy League education. Mama is an artist who works with found and salvaged materials. She is a stranger who makes dream catchers from wire and the broken body parts of porcelain dolls and the bones she finds around the property. While the kids I went to school with had young hip parents who drove Porsches, snorted cocaine on the weekends, and listened to the Talking Heads simply because they were told by the other talking heads that they should, my parents owned and operated a mystery bookstore; my dad didn’t know how to drive, and when he didn’t get a ride from my mother in her puke-colored rusty Volvo, he rode a bicycle, walked, or took the bus. My mother was not only as old as some of my peer’s grandmothers, she was six years older than my dad (a no-no in any patriarchal culture). Back then ALL mothers were young. Now everyone is having kids later on in life and the norm is still for the male in the relationship to the older one. My parents listened to Utah Phillips and John Prine, gardened, boycotted Campbell’s and Nestle, and baked brown loaves of whole wheat bread. We were part of the X class while everyone else (with a few exceptions) were filthy 80s rich, as in they lived in mansions; as in, they were all about materialism and brand names.

If only Fig and I had been able to disappear life might have been easier for us both, but instead our classmates noticed us; they noticed every way that we were different. One of these things is not like the other. We weren’t in the spotlight but under the microscope instead and everyone was looking at us and everyone had shiny sharp scalpels and they didn’t hesitate to dissect us to see how else we might be different. In a way, they acted as our mirrors. They showed us new ways to see ourselves. They were not forgiving like the moon or the candlelight Plath calls, “The liars,” in her poem.

In the book, Fig is trying to touch her classmates because the Calendar insists on it when the Challenger lifts off and falls apart on the television screen in front of her. I was sitting at my desk when the principal came over the intercom to announce the catastrophe. There was a boy from our school, from my grade even, who’d gotten to go to the Kennedy Space Center to see the shuttle leave our atmosphere. He was somewhere in the crowds of people in the footage I watched on YouTube when I researched the event for the scenes I wrote in Fig years after the disaster had happened. The principal told us that we would remember this day for the rest of our lives. Like the principal at Fig’s school, he led us in a moment of silence. My teacher then told us where she’d been when Kennedy was shot. I’d heard my dad also tell the story of where he’d been too, how he wrote about it for his college newspaper, then had too much to drink and crashed through a window. It wasn’t until I was older that I learned the specifics of this story, that he’d been trying to undress his lover when he broke through the glass. My teacher said, “You will remember this forever. It is your equivalent to my Kennedy.” 9/11 is my stepdaughter’s equivilant to my Challenger, to my parent’s generation’s Kennedy. These events thread through us as a common experience, a shared narrative–they connect us. Like alchemy, they make all the differences suddenly, but unfortunately only temporarily, something valuable.

We make contact with each other when we talk about it, a connection we normally wouldn’t make. When we say, “I was sitting at my desk at school when the Challenger happened,” we all nod.

I can still remember the slant of sun coming in through the windows and the way the static crackled on the intercom when the principal made the announcement. I remember how my teacher looked at the ceiling like she was trying to keep her tears from falling. What do you remember?

When the first plane hit the Twin Towers on September 11th, 2001, I was still asleep. And I was asleep for the second plane too. A mother with a baby at the time, I remember shuffling out of my bedroom to get a cup of coffee and wondering why my husband was glued to the television at such an early hour. When I sat down next to him, the replays were beginning, and the next thing I knew we’d been watching the attack over and over again for hours, hooked. When my nine-year-old stepdaughter picked up my one-year old daughter and flew her through the sky of our tiny living room into the two towers she’d made from the same set of wooden blocks I’d played with as a child, I knew it was time to turn the TV off. Where were you? Who were you with? Who were you worried about?

Also, please note the television I just mentioned in the paragraph above; this is the television with the tinfoil wrapped antennas I was describing before. The one I wrote into the fabric of Fig’s classroom.

My former writing teacher, Junior Burke, used to talk about the emotional truths that show up in our work. After he read my creative thesis he’d asked me how much of it was true and I was offended. I thought he was doing what so many male editors have done before when they assume I’m writing memoir when I am not. They even send the work back and say, “Sorry, we only publish fiction” as if I was writing something else. But then Junior clarified what he meant. He said the emotional truths are the bits of ourselves that slip into the writing. For example, when Fig goes home after watching the Challenger explode at school, her mother, who’s been doing so well as of late is starting to unravel again. Fig thinks this is because she’s been failing the ordeals. When Mama sits there, watching the news and the Challenger breaking apart again and again, the emotional truth is how I watched the planes fly into the World Trade Center, on repeat, obsessed. There is an emotional truth in the connection Fig and I have over Zilpha Keatley Snyder and the calendars we made and religiously followed. Furthermore, I am connected to her mother by emotional truth just as much, if not more. Mama is me questioning myself as a mother and a feminist. I make art from broken things. I talk about Chinese footbinding. I worry I overload my daughters with too much information, too soon. I might not be schizophrenic, but I do hear voices. I heard Fig talking to me three years ago. Her voice wasn’t the same as the voice my thoughts used. I literally listened to her change as she grew up and I had no choice but to write down what she had to say.

In class today no one wanted to share the “Mirror” poems they had written. I didn’t expect that they would. I asked, “Did they come out super personal?” and they all nodded. Most of them looked sad. What they might not know is that the truths they recorded today will resurrect in other works–that is, if they keep writing. I hope they keep writing. Please, keep writing. Don’t stop.

Many of these same students are still struggling with the practice of “free writing” or “automatic writing” as Gertrude Stein liked to call it. What I’ve realized from working with beginners again is how much I still free-write. I free-wrote my way through Fig, and I’m doing the same with Roadside Altars. Writing this way is the only way to call upon the muse, to hear the voices you need to hear, and to plumb the recesses of our hearts and psyches for the emotional truths that are lingering there just waiting to be delivered.

My editor tells me that YA set in the 1980s and 1990s is hot right now. All the rage. Indeed, on GoodReads I’ve watched Fig pop up on lists titled exactly that: “YA set in the 1980s” and “YA set in the 1990s.” My publicist thinks it’s because there’s been a resurgence in 80s fashion, but I think something else is happening. I’ve also read that 2015 is going to be the year of feminisn in YA. I think the writers writing these books are my age. We’re writing the landscape of our youth. We’re writing our shared narrative. We are writing what we know and that is where you’ll find the truth and all truth is emotional even if the truth seems to be a lie like a work of fiction seems to be a lie when it is anything but; the truth is what makes the page begin to shake; the truth vibrates and hums; it trembles and screams and laughs and cries and rages and sighs, and sometimes, it sings.